Phoenix LGBTQ+ Community Suspicious After Sports Tournament Broken Up by Park Ranger, Police

Excessive intervention by police officers and a Phoenix park ranger during an LGBTQ+ sports tournament Sunday night left players uneasy and confused.

Maudie’s is modeled after a decades-old lesbian bar, but its mission is less about drinking and more about community.

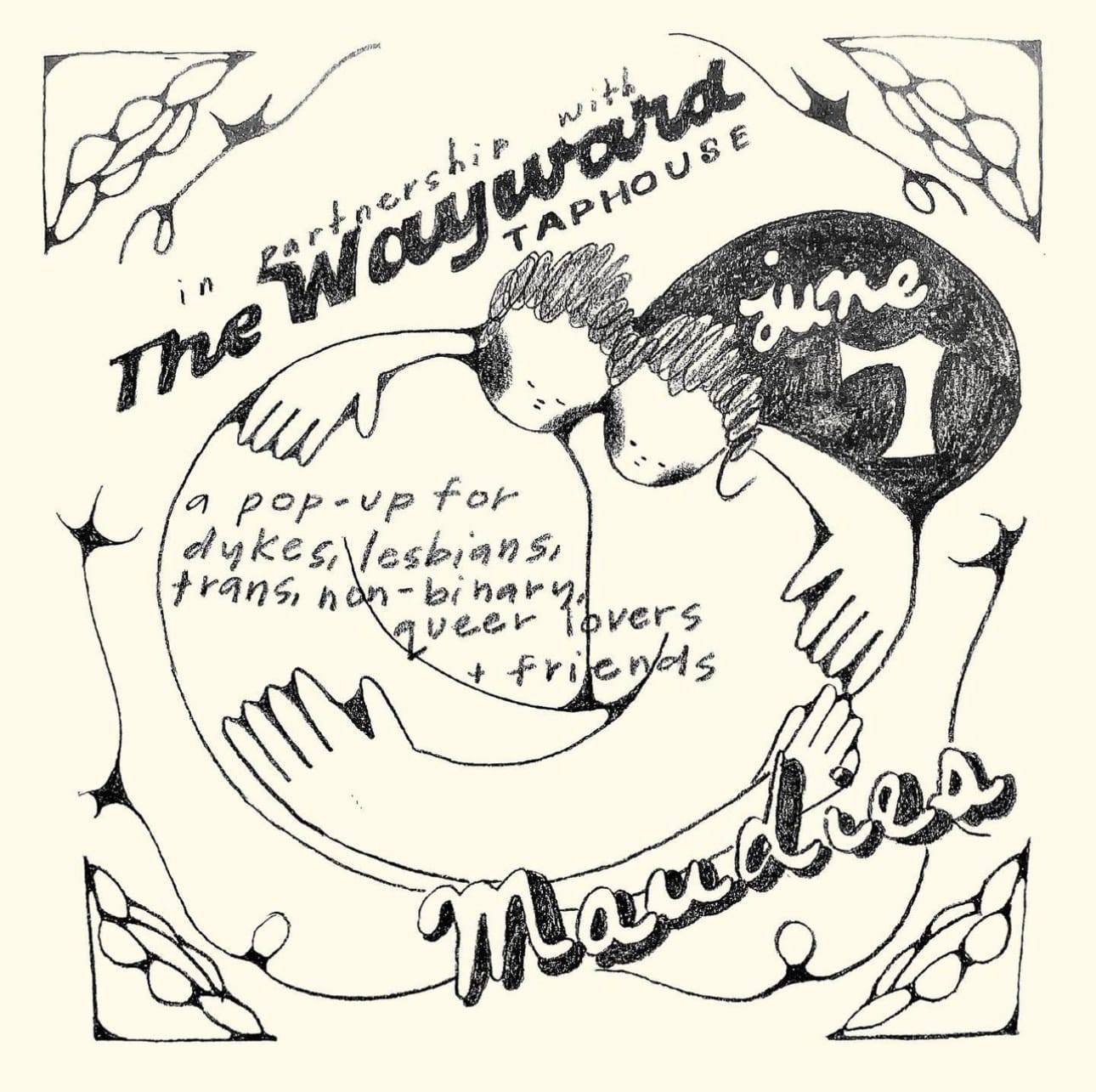

As soon as you enter Maudies at The Wayward Taphouse, you know something is different. The bar pop-up, which launched last June, is inspired by Maud’s, the iconic lesbian bar in San Francisco. But here they're not just lesbian, they are also queer, non-binary, and trans.

No one is turned away at the door for how they identify. There are no glares.

At Maudies, creator Abigail Spong is building on Maud’s legacy of what it means to be a safe space for the LGBTQ+ community in Phoenix.

Businesses, especially gay bars, often tout they are “safe spaces,” a stamp of approval where queer folks can be and express themselves freely in an establishment without the weight of fear, shame, or harassment.

That’s not quite true, though, as LOOKOUT’s reporting exposed how multiple people—especially those who are femme or female presenting—discussed their own mistreatment inside the very same spaces.

So, what does it mean to be a “safe space,” especially because what one person considers safe can easily be construed as unsafe for someone else?

The concept of “safe space” originated in the gay liberation and women’s movement during the mid-1960s. In her book, “Mapping Gay L.A.”, scholar and activist Moira Kenney defined these various spaces as a “certain license to speak and act freely, form collective strength, and generate strategies for resistance.”

The term refers to places “intended to be free of bias, conflict, criticism, or potentially threatening actions, ideas, or conversations,” creating a safe space for marginalized people. Ultimately, it’s an extension of comfort for those outside of dominant spaces and normative social identities that may be subject to some form of abuse, discrimination or harassment.

Before the famed 1969 riots at Stonewall Inn in New York City—one of the birthplaces of the gay liberation movement—there was one such safe space called Maud’s in San Francisco, a lesbian bar that claimed to be the oldest one of its kind in the United States. As the subject of the 1993 documentary “Last Call at Maud’s,” Maud’s was considered a safe haven at the time, where patrons were known as “Maudies,” and formed what would become the Gay Softball League. In the film, patrons reminisced about their experiences and the bar’s role in women’s and LGBTQ+ history.

It was a place of common ground and understanding.

Owner Rikki Streicher, a lesbian and gay rights activist, tended the bar herself even though women were not allowed to be employed as bartenders in California until 1971. In “Last Call at Maud’s,” Streicher spoke about the backbone of her bar: “I've always felt that bars were the most honest, open, free place that women could go.”

When Spong began hosting Maudies at The Wayward Taphouse, a queer-run bar in downtown Phoenix, she held the queer history of Maud’s close to her heart. Her deepest desire, she said, was to honor the original Maud’s and continue where it left off, cultivating a safe space for the LGBTQ+ community in downtown Phoenix: “I wanted it to be intentional,” Spong said of her vision for Maudies.

Spong, who had pitched her idea to Wayward Taphouse co-owner Hilda Cardenas and operations manager Serena Fonze, said that she wanted to create a similar experience to Maud’s, but with even more intention, inclusiveness and purpose.

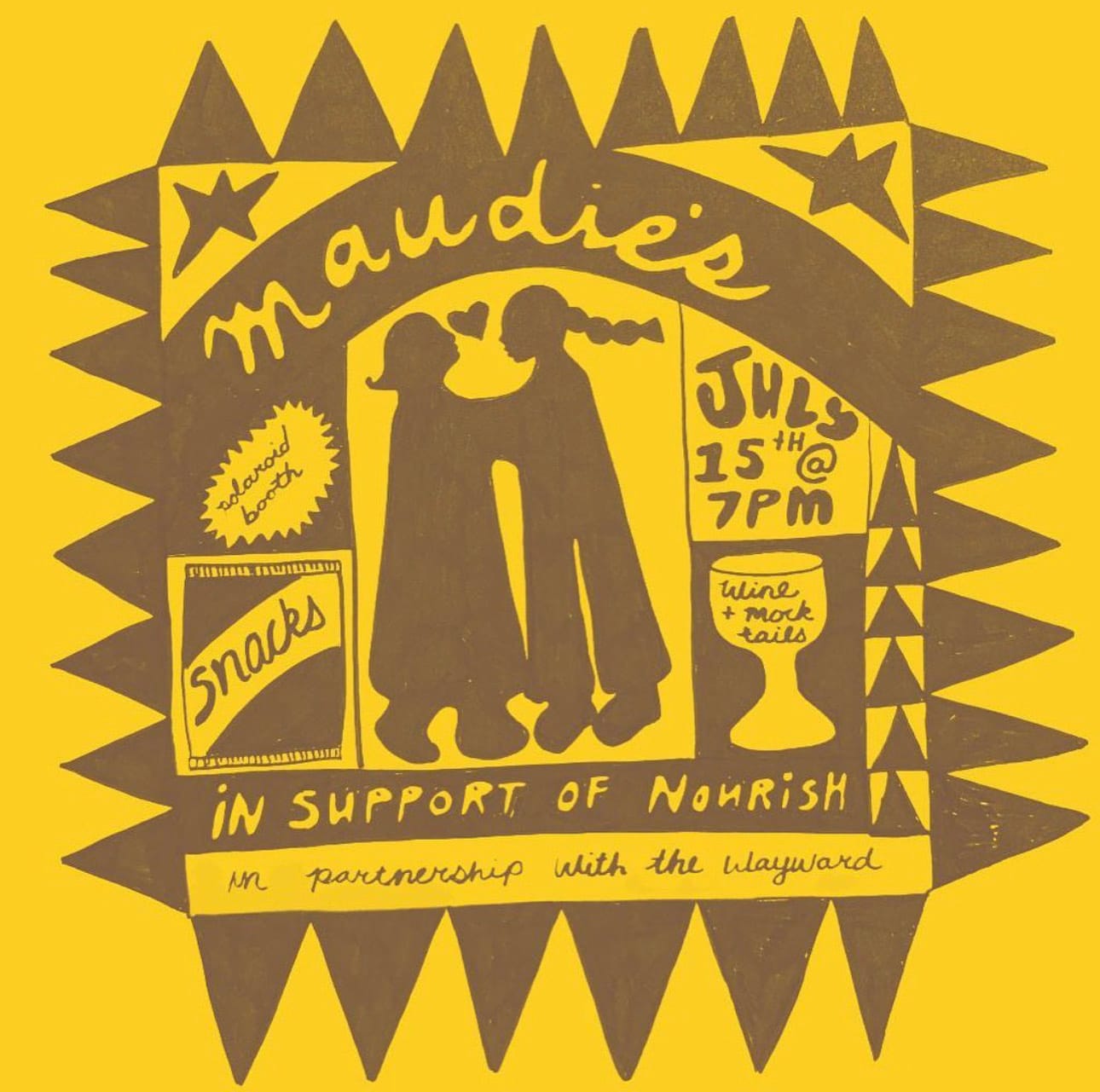

Spong often uses queer artists to showcase Maudies events. Illustration on left by Wolfe. Illustration on right by Leika Kitamura.

“A bar scene can be easy and approachable for a lot of people and it’s also such an integral part of gay culture,” Spong said. “I feel like the bar and club scene is very important to our history, but I think that the queer experience is so much more vast than that.”

It was important to Spong, who is an advocate for sobriety, to offer non-alcoholic options, including one that is free of charge.

“The point of Maudie’s was to start it as a bar pop-up,” said Spong. “But to include different things, have different legs, and branch out in different ways.”

Because more people within the LGBTQ+ community suffer from discrimination, hate crimes, social rejection, isolation, healthcare inequality, and everyday life challenges, a large portion of the community suffers from depression and anxiety, inevitably leading to an increased risk of substance use disorder.

Spong said she wanted to recognize Maudies as a “holistic, casual and conversational” event without the pressure of drinking alcohol in order to socialize.

In addition, there is a Maudies group chat on the social media app Geneva which gives guests another way to meet and interact outside the pop-up events, because “unless you’re on a dating app or going to a bar, it’s hard to meet other queer people,” Spong said.

With more than 200 members and several different chat rooms—Book Club, History Lesson, and Missed Connections, to name a few—the online group provides members a comfortable and convenient way to connect digitally.

Since Maudies started in June of 2023, Spong has received an enormous amount of positive feedback from guests. One patron interviewed at the event commented on the successful pop-up bar by saying it was, “the most positive experience I’ve had…they’re doing what a lot of other places have not.”

Maudies has expanded on what it means to be an inclusive and accessible space for queer folks, continuing to evolve with intention for the community that it serves. By acknowledging that there are always ways to improve and encouraging an open dialogue between guests and the organizers, Spong recognizes that though safe spaces aren’t always guaranteed, we can all strive to build one as a collective.

Local patrons have noticed that Spong’s mission for Maudie’s is a departure from other LGBTQ+ bars it competes with.

“There aren’t enough queer spaces where alcohol isn’t involved.” said Amanda Smith, a member of the queer community in Phoenix. “There are a lot of people in the queer community who are disenfranchised, who are more prone to turn to substance abuse, and drinking is way too normalized.”

“It doesn’t feel like I’m at a club,” she said. “It’s not about drinking so much, it’s about socializing. Everyone’s just hanging out and talking. It’s a good vibe.”

Leo Fulwider, another Maudies-goer who identifies as non-binary and transmasc, said that while at the gay Sountry-Western bar Charlie's, it was a “shocking and jarring experience” to be turned away at the door for not paying a cover because their state ID identifies them as female.

“I walk to a place like Charlie's, and quite literally at the door, I am being forced to explain my identity,” Fulwider said. “That should not be happening and that should not be happening for any trans person who walks into that establishment.”

For Fulwider and many other members of the LGBTQIA+ community, searching for a safe space is sometimes exhausting and violating, even within places that advertise themselves as a “gay bar”.

“My intention coming to spaces like that is ideally to be around folks who are on the same page as me, who share similar values, who are interested in creating a space that is truly inclusive for everyone,” they said. “Where I can be myself.”

LOOKOUT Publications (EIN: 92-3129757) is a federally recognized nonprofit news outlet.

All mailed inquiries can be sent to 221 E. Indianola Ave, Phoenix, AZ 85012.