Citing Funding Risks, Clinics Cancel Gender-Affirming Treatment for Adults

One adult patient of Planned Parenthood Arizona was told by phone Friday night that the treatment she receives for gender-affirming care was "paused."

River Chinnui is a nonbinary teacher in Peoria who has been the center of anti-queer rhetoric. Now, they’re making their voice heard.

On July 13 of this year, River Chunnui decided to do something they had never thought about before: stand in public at a school board meeting and tell their side of the story.

“I just was terrified,” Chunnui said. “I was so scared.”

For months, Chunnui, who is nonbinary and who uses they and them pronouns, had been the target of fearmongering, specifically by two school board members in the district where they worked.

Chunnui looked both Heather Rooks and Rebecca Hill in the eye, describing what it was like to be on the receiving end of a hate-filled campaign against gender identity.

“Let me be clear,” Chunnui said. “The past year has been nothing short of two members of this very board lobbying against a subgroup of individuals and children simply because of who they are. This is the very definition of discrimination. And this discrimination, prejudice, transphobia and hatred for other–”

“Point of order,” Hill interrupted. “Point of order. You're not allowed to call me transphobic. That's a slur.”

Rooks came to Hill’s defense, “Yes, if you could just please refrain from comments made against those–”

The crowd of a few dozen people screamed back: “Shame on you!”

The people had had enough.

Through social media posts and their known position on Peoria’s Governing School Board, Rooks and Hill have attacked trans kids in schools and on sports teams. They have used religion to promote extremist ideologies in a public forum, garnering the attention of Turning Point USA, a far-right religious and political group that denounces the existence of trans people.

As the audience moaned in defiance, shrugged, and rolled their eyes, Rooks raised her voice: “Excuse me! If you continue, I will ask the officer in the back of the room to remove you.”

Chunnui continued to address the room. “We have a moral responsibility to speak out against discrimination and injustice, even when those who commit such acts are in positions of power. The consequences of silence are too high for queer and trans students who already experience higher rates of depression and suicidal ideation. Our students, our children, are watching us and counting on our voices.”

Since coming out publicly at work two years ago, Chunnui, a special education teacher who has taught in Arizona for more than a decade, has been a target. Both local far-right elected officials and evangelical Christians called for Chunnui termination online and during school board meetings.

At first, Chunnui avoided the spotlight, fearful that speaking out would put their two daughters in harm’s way. But violence eventually found them.

The stress of coming out and the hostility from people they didn’t even know became so unbearable that last November, Chunnui tried taking their own life.

Chunnui's experience is far from isolated. In interviews with dozens of students and staff across Maricopa County, LOOKOUT has learned that the experience for trans people attending (and working at) public schools has become tenuous, at best. It coincides with the spate of anti-queer rhetoric and legislation nationwide over the past year.

In Arizona alone, state legislators have passed 12 bills to limit queer visibility in public and private spaces. Although Gov. Katie Hobbs vetoed all of the legislation, it is cold comfort to people like Chunnui, who have been navigating public life in the middle of a one-sided culture war.

The most heated public debates are happening at school board meetings and public meetings in which religious groups and individuals are using scripture to shape public policy. Meetings like the one at which Chunnui spoke.

As a result, the increased harassment and false information said regarding LGBTQ+ issues in the meetings has resulted, anecdotally, in the rise of violence. Chunnui knows first-hand about, with threatening emails and phone calls, car tires slashed on school grounds, and rock-smashed windows at home.

But with a new-found self-advocacy, Chunnui has decided to fight back and stand up against the same people who would rather see them—and others like them—go away.

Chunnui became a teacher more than a decade ago. Helping children learn about themselves and watching them grow is part of what makes the job so rewarding. But working with kids who have special needs is the personal fulfillment of a professional dream. In 2021, Chunnui secured the teaching job in Peoria they had always wanted.

“I was set on getting a job in Peoria at Desert Harbor,” Chunnui said. “I knew the people that worked there, I knew the work that went into that school, and I knew that I could excel there.”

Around that time, Chunnui was also on a personal journey. Words like “transgender” and “nonbinary” were brand new to the cultural lexicon. For Chinnui, these words were relatable, at last.

As a child, the idea of being a girl or a boy didn’t compute with Chunnui. One night, their mother sat down with an anatomy coloring book and talked about the differences between boys and girls. When their mother wasn’t looking, Chunnui grabbed a pair of scissors and began cutting and pasting body parts.

“This is me,” Chunnui remembers saying to their mother, proudly. Their mother said it wasn’t possible to be both.

That moment stuck with Chunnui their whole life, and made the transition to identifying as nonbinary difficult, both personally and professionally. With two kids at home and being newly divorced from their husband, trying to solve personal issues with managing a new identity was too difficult a task to wrangle. Chinnui originally came out as a lesbian to test the waters of coming out.

But it wasn’t enough because it wasn’t fully true.

As the COVID pandemic settled, so did Chunnui's anxieties over the world’s perception of them. That same year they got the job in Peoria, Chunnui came out as nonbinary to their boss.

At first, there was acceptance. When Chunnui asked if they could announce being nonbinary to the staff in an email, the principal, Chunnui said, shifted a bit.

“I don’t know,” Chunnui remembers the principal saying. “Let me talk to the district.”

A few days later, they were authorized to send an email explaining their pronouns. It was then Chunnui took on the name “River” publicly.

“It felt so freeing,” they said.

The students were unfazed. Chunnui explained that they would simply go by “Mx” instead of “Miss.” There weren’t any questions, no talk about genitals or the intricacies of gender dysphoria or class discussion on if girls are indeed just girls.

But Chunnui's announcement did not sit well with the school district.

When Markus Ceniceros was in the eighth grade, his teacher hung a sign outside the classroom. He remembers it was a rainbow flag, and it meant one thing—that people like Ceniceros were safe.

The sign didn’t appear randomly—it was there because members of the Littleton School District community in western Phoenix were unhappy with the presence of gay teachers and a gay principal, Ceniceros said.

Ceniceros, now 19, remembers the conversations the sign sparked in his school, that being gay wasn’t OK, and it was an affront to God. A week after it went up, the sign was removed. The message to Ceniceros and his classmates was clear: They were not welcome.

“I don’t want kids to have to go through what I went through,” said Ceniceros, who now sits on a school board as one of the state’s youngest elected LGBTQ+ individuals. He governs the same district where he once closeted himself, in Littleton. The rhetoric around queer people’s existence in public has only heightened, he said..

This year, Ceniceros tried to push for a statement of support for queer kids during Pride month. He tried to bring up his own experience as a gay young boy in Arizona, and how there was immense fear and shame. It didn’t get the votes.

Although his stories have shed light in school board discussions, they have not helped push the narrative that queer kids do exist, and that they need to feel welcome and safe when they enter a classroom.

“If we are leaders in learning, we have to learn from every student's experience,” he said.

The Littleton School District is in Avondale, about 20 miles away from Peoria. The cultural climate and discussions around queer visibility are just as prevalent there as they are in Peoria, showing that the discussion has permeated almost every part of Phoenix’s various education boards.

School boards from Gilbert to Glendale have experienced a wave of people showing up at school boards or town halls, using religion and conservative talking points to denounce the experiences of trans kids using public bathrooms or who can play in sports.

Last month, LOOKOUT published data that shows how in the Peoria Unified School District, religious words, such as “Jesus,” “God,” “church,” or “Bible,” were brought up at least 47 times during board meetings between February and August 2023 in an attempt to sway votes on agenda items related to LGBTQ+ issues.

These same people attempted to get Chunnui fired from their job for simply sending an email about an honorary national holiday.

It was March 31, 2022, International Trans Day of Visibility.

When Chunnui arrived at work, they saw a handful of students congregating outside of the school dressed in teal, white, and pink, the colors of the transgender flag.

(This year, President Joseph R. Biden released a statement proclaiming March 31 a national holiday honoring trans people.)

On the same day that the kids stood outside their school showing their pride, former Gov. Doug Ducey was miles away at the state Capitol and refused to acknowledge that trans people even existed. Instead, he doubled down on two bills he signed: one that banned gender-affirming care for youth, and another that banned trans girls and women to play in girls’ high school sports.

“We have trans kids on our campus and in our district. What does that say to them when they don’t get any kind of acknowledgement?” Chunnui asked, “I was just thinking to myself that teachers probably should just be aware of why a number of students are dressed like this.”

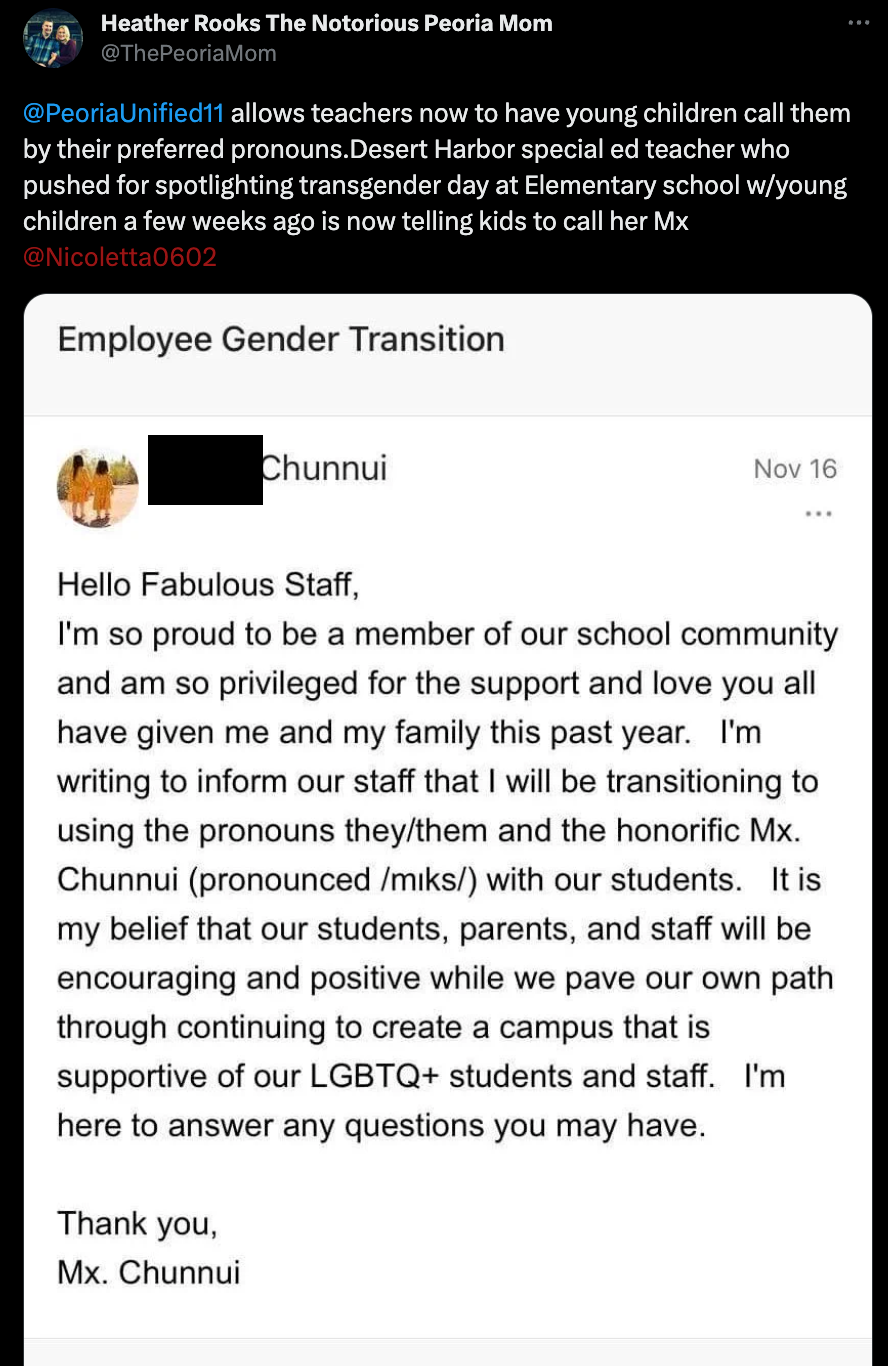

In an email, Chunnui wrote to the school staff:

“Hello Fabulous Staff. I just wanted to let you know that you may see our students wearing more pink, teal, and white today. Today is a quickly growing annual event called ‘International Transgender Day of Visibility.’ Our President is expected to make some announcements today on new [legislation] to protect the rights of Trans students…many of our students have taken a keen interest in these legislative movements. How can you help? If you notice a student purposefully wearing the colors of the trans flag, a simple ‘I see you’ or ‘I support you’ can go a long way. Thank you fabulous staff!”

The email didn’t seem ground-breaking. It was, by all accounts, an “FYI.”

People often sent emails to the entire staff about upcoming fundraisers, personal life updates, and any news to share on or off campus, Chunnui said. This email, telling teachers about an honorary holiday, seemed equally on par.

But the email was leaked to far-right evangelical and conservative talking heads in addition to local elected officials going as high as the state Senate.

“No level of sexuality or lifestyle should be pushed onto little children. I don’t care if they are pushing for heterosexuality. Leave our kids alone. Teach them math, reading, and science,” said Warren Petersen, the leading Republican state senator who represents Gilbert. “These actions are completely inappropriate as someone who is in a position of trust with our children.”

Facebook and Twitter posts attacked the teacher and the school district, calling Chunnui and the other teachers “groomers” and sexually exploiting kids.

But Chunnui, who had gone home sick with COVID a few hours after sending the email, had no clue that anything was wrong until days later: “I got a phone call several days later, because I was quarantining, from the principal saying, ‘Hey just letting you know the news got ahold of your email’.”

The email circulated among far-right news sites, such as AZ Free News, and was being parroted by people who normally espouse and legislate anti-trans policy, such as Peterson.

Chunnui was confused. “I didn’t really understand at all, because I felt my email wasn’t negative in any way,” they said. “I didn’t feel it wasn’t educational, and I felt it was necessary for our teachers to know why a small group of students was dressed that way.”

By the end of the day, Chunnui was placed on administrative leave, pending an investigation.

“It was devastating,” Chunnui said. “My identity is tied to being a teacher. Much of my friendships are with my community of teachers. And when you’re on paid leave, you’re not allowed to talk to your co-workers. You’re really taken away from your community.”

Meanwhile, school board leaders such as Rooks and Hill began their campaign to remove Chunnui.

Rooks, who often re-tweets posts from the LGBTQ+ hate group Moms for Liberty, received a copy of Chunnui's original email sent out to staff about their transition and posted it on Twitter with Chunnui's full name.

Chunnui's birth name was exposed and said out loud during board meetings, and was posted online. Hate-filled emails, sent to both their personal email address and official school account, flooded their inbox.

An investigation sanctioned by the school district made Chunnui's life harder, they said, explaining that the process and the questions asked were “unfair” and “felt political.”

The investigator asked questions about Chunnui's email: why they sent it, their curriculum, and what books were read.

“She kept asking, ‘are you teaching pronouns’,” Chunnui remembered. “And I just kept saying no.”

The investigator asked why Chunnui decided to read a book about boys wearing pink on a public reading day. Chinnui explained that the choice was made by their own child, and it was broadcast over the district’s YouTube channel without repercussions.

By the next year, in an April public meeting for the school district, Hill and Rooks both motioned to rehire a roster of teachers except for Chunnui and one other teacher.

During that board meeting, a rock went through the window of Chunnui's home, according to a Peoria Police Department’s report.

“I didn’t know how to compartmentalize it all. I was just prioritizing keeping my job,” Chunnui said.

The stress of being called out publicly and having their reputation questioned took a toll on on Chunnui's mental health. Soon after, Chunnui took a handful of pills and tried ending their life.

A speedy phone call to friends saved Chunnui, who stayed in an inpatient psychiatric care facility for a week.

The suicide attempt wasn’t going to be a moment of failure for Chunnui. Instead, they used it as an opportunity to grow and advocate for themself and other students. They decided to fight back and put an end to the abuse.

In July this year, Chunnui filed a civil complaint against Peoria Unified School District and board members Rooks and Hill.

The complaint asks for $50,000 in damages and an additional $1,000 from both Hill and Rooks.

Hill has since resigned from her position on the board.

On August 13, 2023, Chunnui stood in front of a large crowd for the second time. Rather than addressing the people who had drove them to the lowest point in their life, this crowd was there in support.

Flanked by cameras and photographers, they fumbled with a megaphone; speaking still wasn’t a strongsuit, and they relied on reading from a phone.

But Chunnui had a lot to say, and a little bit of stage fright wasn’t going to stand in their way.

The crowd—which had gathered to support Chunnui's battle against the Peoria Unified School District—cheered and waved signs, calling for an end to queer-based hatred.

It was a moment Chunnui had been yearning for—acceptance among a crowd of people that saw them for what they were, not just how they labeled themselves.

Standing outside Desert Harbor Elementary in Peoria, the school Chunnui worked so hard to be part of, their voice shook slightly when starting to speak. Their message was clear. They took a big breath in, and yelled: “My name is River Chunnui and my pronouns are they, them!”

A version of this story in the magazine misspelled Chunnui's last name. We regret the error.

LOOKOUT Publications (EIN: 92-3129757) is a federally recognized nonprofit news outlet.

All mailed inquiries can be sent to 221 E. Indianola Ave, Phoenix, AZ 85012.